Millions of pirate treasure around Cuba and Porto Rico

This story was told in an article dated 15 January 1899.

Our new islands in the West Indies furnish one opportunity for Yankee speculative genius that has been curiously overlooked. On the submerged rocks and reefs and in the dangerous passages around Cuba and Porto Rico lie untold wealth — millions of dollars in gold coin, silver bars and jewels. In the past Spain's rapacious rule has prevented the recovery of much of this although several men have been made millionaires by the findings of divers in Cuban waters.

During the early years of Spain's rule in the New World hundreds of galleons sailed yearly from Mexico and the shores of South America for Spain, stopping at the ports of Cuba and passing out into the Atlantic through the Windward Passage.

For more than century there was a close rivalry between buccaneers and the hurricanes to see which could sink the greater number of those treasure fleets. In many cases the location of the wrecks is now definitely known, while in many other the records at Madrid and at Havana show the location only approximately. West Indian waters outside of the harbors are exceedingly clear, so that it is oftentimes possible to see to the depth of eighteen or twenty feet, making it easy for divers to make the necessary exploration.

Indeed with some of the recently invented submarine boats, such a boat, for instance, as Simon Lake's Argonaut, which crawls on the bottom of the sea, it would be a comparatively easy task to prowl around on the bottom of the sea and discover these old wrecks and loot them of their gold.

Lost $1,000,000 Every Year.

A little research into the musty records of Madrid show that during the early part of the seventeenth century over thirty million dollars' worth of silver alone was shipped to Spain. During the latter part of the seventh century one mine, the Valenciana of Guanazuato employed 4000 slaves, and the company owning it lost $1,000,000 every year by pirates and accidents at sea without in the least impairing its credit in European markets.

Most of these enormous losses strew the ocean bottom around the West Indian islands. A careful search of old Spanish records would reveal the approcimate location of scores of the treasure wrecks, so that they could be visited with very little difficulty. My researches have been limited to such ancient Spanish records as may be found in America, and from these alone — and their number compares with the immense libraries of such works in Madrid as a drop to a stream — I have unearthed the stories of more than a score of vessels and fleets, the wrecks of which now lie in American waters.

Fleet of Treasure Wrecks.

Bast of the Isle of Pines are the Gardinillos, or famous Jardine rocks, where lies a whole fleet of good ships. It was here that the daring buccaneer captain, Barthelome Portugues, lost the richest prize he ever took in his adventurous career, and it lies there today, awaiting the lucky submarine explorer. The account of the wreck in the old books is most circumstantial. Barthelome Portugues had fitted out a small three-pounder vessel at Golfo Triste, on the Gulf of Campeachy, and with a crew of thirty men he had captured a treasure galleon bound from Carthagena to Havana.

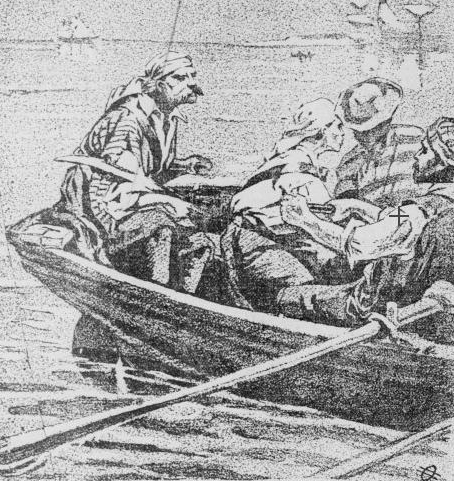

It was a lucky adventure. The inventory of the ship's goods showed over a hundred thousand dollars' worth of gold and silver bullion, with as much more in coin. Portugues set his sails for Tortuga. but as they were passing Cape Corrientos three swift sailing guard vessels from New Spain swept down upon the ship and captured him and the entire crew, and took them in irons to San Francisco in Campeachy. The old account tells how Portugues escaped that night, and after an almost incredible journey through the swamps, secured a canoe from a friend, enlisted thirty men and actually recovered the ship that had been taken from him.

Then he sailed away again for Tortuga, that island of blood and spoil. Off the Isle of Pines a hurricane brought down vengeance upon him and carried him irresistibly on the Jardine rocks, and the galleon with all its treasure went down. Some of the hardy buccaneers escaped in a small boat to tell the story, but the gold and silver bullion for which they risked so much is still heaped in some hollow .if that rock-bound bed of the sea. This treasure would pay richly for the recovery.

Fifteen Tons of Silver Bars.

Another account of sunken treasure is told as a musty joke in a musty tone. In 1650 three canoes, manned by fifteen bucca- neers, each crept around the western end of Cuba and came suddenly upon one of his Majesty's treasure ships, bound from Caracas to Havana. They swarmed over the side of the great vessel like so many rats, and threw every Spaniard overboard.

The uncouth visitors ransacked the vessel for booty, but to their disgust, found only a small quantity of wine in the officers' quarters, and in the hold a lot of grayish metal, which some wiseacre on board decided to be tin ore, and not wishing their newly acquired vessel to be laden with such trash, the leader ordered it to be thrown overboard, and there it lies to this day, not far from the Colorado banks, not less than fifteen tons of fine silver bars.

Phipps' Enormous Fortune.

Sir William Phipps, a baronet of New England, who was once Governor of Massachusetts, enriched his ancestral house and left his descendants among the wealthiest in New England by sharing the secret of a smuggler, who saw a plate fleet go down in a storm, about half way between the nearest points of Cuba and Haiti. "Phipps' fortune" has been famous ever since. And yet it is said that he found only one of the sunken ships of the fleet containing not less than thirty-two tons of silver, with jewels enough to make $2,000,000.

The remainder of the vessels still lie off the eastern point of Cuba, and they are estimated to contain many millions of dollars. Millions in Bullion. Another treasure wreck is the center of. a most romantic and thrilling story of crime. In the year 1717 Charles Vane, a notorious pirate of the West Indies, captured about $80,000 in pieces of eight that were being taken by divers from one of five plate ships that had gone down in a storm just east of Key West. The silver bars, as they were brought to the surface by divers, were stored in a little fort on the mainland to await the Guardacosta, which was carrying: the treasure in installments to Havana.

Vane learned of this and made a sudden descent upon the fort, captured the treasure, rowed out to the vessel where the divers were at work, captured the ship and sailed away, leaving the destitute crew and divers marooned on the barren key. The plate fleet of five galleons, on which these divers were working, was carrying $4.000,000 in bullion when it was wrecked, and less than a fourth was recovered and captured by Vane. The old records estimate that $3,000,000 still remains in the sea at this point.

Treasure Galleons.

Another circumstantial but incomplete report tells of the wreck of several treasure galleons in the Gulf of Florida in 1676. Of this treasure eight million dollars in pieces of eight were recovered and carried to Havana. Fifty thousand more after being stored on the shore were captured by the famous Captain Jennings, who had hastily equipped three sloops in Jamaica. After this assault the Spaniards abandoned all further work on the sunken galleons and lost all knowledge of their exact location. There is no question that a little exploration here will reveal this sunken fleet, which still contains, according to the old records, several million dollars in gold and silver.

Another Rich Wreck

Somewhere a few miles southwest of the Isle of Pines there is a princely fortune in diamonds and gold awaiting the hunter who will travel the bottom of the Caribbean Sea and cast a searchlight carefully over the hulls of sunken treasure ships. It is the remains of a Spanish ship in the royal service, whose commander, Don Sebastian Jeminez, touched at Santiago de Cuba in 1560, on his way to Spain. He was carrying the "king's fifth" from the silver mines of Guanacaboa, amounting to nearly twelve tons of good silver bars and unknown but immense quantities of personal treasure shipped by homegoing merchants.

Upon sailing from Santiago he was caught in a terrific tempest which tore the ship from its anchor and drove it upon the rocks within sight of the observers on the bluffs at Santiago. No vestige of ship or crew was ever seen again. The galleon probably lies not far from the recent naval battleground between the Spanish and American fleets, and it offers a princely lure for the bold submariner who will conduct a patient search.

Richest Treasure Ship.

Another, and probably the richest of all treasure ships lost in the West Indies, was wrecked in 1679. A notable company of officials, ecclesiastics and citizens of New Spain were on board, bound for Spain, at the invitation of the King. They carried the most costly personal possessions. The record tells of diamond crosses of enormous value and presents that were to win the favor of the great King of Spain, besides many tons of silver bullion, which was actually used as ballast.

But many times richer than all these were the bars of gold which most of the officials were carrying with them back to Spain, in the hopes of living the rest of their days in distinguished opulence. One of the ladies, Dona Inez Escobedo, was taking with her an Indian slave as a present for her brother, who was governor of one of the Canary Islands. The few negro slaves on board were servile enough, but the Indian, whose name the records do not give, was unmanageable and grew more obstinate at every punishment.

One morning, when the ship was a few leagues southeast of the Isle of Pines, the captain was horrified to find that water was pouring into the hold. He was about to descend through the hatchway to discover the cause, when the warning voice of the Indian declared that the first man to appear through the opening would be shot. Immediately those who gathered about heard the blows of a hatchet upon the bottom of the vessel.

The horrible truth then dawned upon them that the untamable Indian intended to escape slavery by wrecking the ship with all on board. They threw down a negro slave, believing that his body would receive the fire of the Indian, but everything above the hatches was plainly visible from the darkness below and the negro lay where he fell, stupefied with fear, while the blows of the hatchet rained faster than ever, and the roar of the water constantly increased in volume.

At last an old officer, Jose Nunez, sprang suddenly through the opening into the hold, waist- deep in water, and charged upon the Indian, sword in hand. He was followed by half a dozen others. They splashed around and finally found the Indian under a beam, beneath the water, where he had crawled and drowned himself. The most frantic efforts were made to stop the leak, but the ship sank, and it was with difficulty that even one boatload of the passengers was able to escape.

Numerous attempts were made by the Spaniards to recover the treasure from this ship, but divers never could find it. These are only a few of many score of similar wrecks, the records of which can be found in the old Spanish reports and histories. They will indicate, in some measure the enormous richness of these hitherto undescribed resources of our new possessions.

Source. San Francisco Call 15 January 1899